Field Trip 3: Hydroplutonic Kernow

Cornwall’s Best Kept Secrets

by Jo Thomas

Our journey into the unfamiliar begins with an exploding map. A straightforward Ordnance Survey style representation of the Gwennap mining district, but with the secrets of the strange complicity between water and the earth’s core hidden in its folds.

It falls to the good people of Urbanomic, and their trusted associates, to reveal the truth of this scarred and traumatised landscape between Falmouth, Redruth and Truro. The clues are layered through the remains of over 200 years of industrial activity and on this blazing hot day in May, we take a tour to piece the story together.

On the way to our first investigation scene, in the ‘wonderful poetry particular to geologists’, James Strongman reminds us of the 300 million years of underground shenanigans that have brought us here today. Collisions of pre-historic continents, gigantic granite batholiths and huge reservoirs of metal rich fluids, all resulting from, as geophilosopher Robin Mackay instructs us, the Hydroplutonic Conspiracy – the complex collusion between water and heat from the earth’s core that is as old as the world itself.

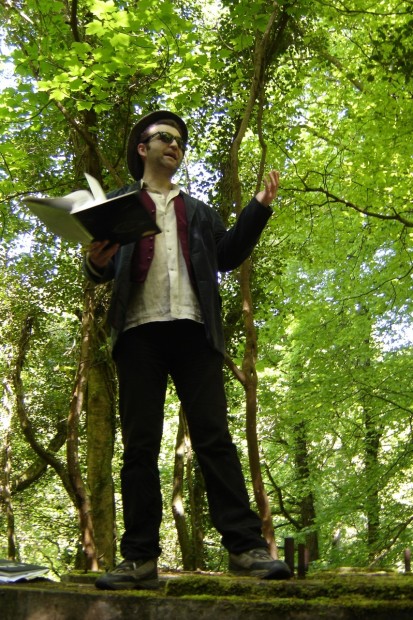

At Kennall Vale, near Ponsanooth the sound of rushing water and the dappled shade of a lush, green forest are welcome sanctuary from the glare of the sun. But this is no place for rest or peaceful reflection. This is a site where the convolution of mankind’s involvement in the Hydroplutonic Conspiracy has racked the landscape. Using the ruins as their pulpit, our guides teach us of the Gunpowder Works that occupied this area throughout the 19th century. Where 60-70 employees, helped by 39 water wheels within a five-and-a-half-mile stretch, exploited the hydraulic capital of the Kennall River to carry out the processes necessary to churn out 4-5,000 barrels of gunpowder every year for use in the nearby tin and copper mining industry.

Shaun Lewin, our party’s Transversal Oecologist, warns us against romanticising the ‘nature reserve’ we see around us. The trees would have been planted to absorb possible explosions at the works, ‘some sort of green blast chamber’ and the whole site is polluted with by-products of the gunpowder making process. Walking through the remains of the buildings and fractured water wheels covered in the fuzz of green moss, embraced by trees growing through their forms, it’s hard not to imagine this as the last traces of some long lost ancient civilisation.

But the works only closed 100 years ago, only just beyond living memory. The fact that the river, which was so valuable to so many people in so many ways, is now merrily gushing its way unfettered through a nature reserve is astounding. Is it a waste of natural energy or a return to the way things should be?

As our journey continues, evidence of Kernowian Syndrome, the local manifestation of the Hydroplutonic Conspiracy, reveals itself to us with a persuasive frequency. At Perran Wharf, established by the Fox family, coal from South Wales to power the steam engines to pump water out of the mines, timber from Norway to line the mine shafts and guano from Peru to provide concentrated nitrogen for gunpowder making were all brought, by water, as close to the mining district as they could get at that time. The nearby Norway Inn is named for its part in this history.

Only a few miles further on at Devoran, we lunch at the spot that was once Cornwall’s busiest port, ‘the main artery of the Hydroplutonic Conspiracy’, during the mid 19th century after the discovery of what was thought to be the largest copper lode in the world. Kenna Hernly tells us of the Redruth and Chasewater railway that carried 60,000 tonnes of material a year back and forth between boats stacked four and five deep and the inland mines. By the 1870s the copper market had crashed and the railway and port went into decline. Now pleasure boats nestle in the old ore bins and the railway tracks hide beneath a very straight road. A level-crossing gate and plaque are preserved, but now just form part of a fence around an empty field. A few of us on the tour try to imagine what it must have been like, but it’s just too much of a leap for the mind to make. Is there any real way to bring something lost back to life, or at least to imagine the stories of the people that walked and sailed this area, and should we even try?

At what’s left of the Point Mills Arsenic Works near Bissoe we settle on the parched ground to hear from philosopher Ian Hamilton Grant about theories that suggest mining and the associated exploitation of the natural world is, in fact, just an extension of nature itself. If we humans are made of organic matter and minerals, then are we nature’s way of creating ideas, the expression of nature’s consciousness? If this is the case, I think, nature must be a ritual self-harmer. The orangey flakes of iron oxide in the stream and the small, grey, metal box monitoring its toxicity levels are a reminder that the repercussions of some of our more invasive ideas continue to pose a threat.

Nowhere is this more apparent than at Nangiles, where our guides tell us of the flash flooding disaster in 1992, when millions of gallons of polluted water spewed up from the many miles of tunnels forming the Great County Adit out into the Carnon River and onwards to the Fal. The oyster industry in the Fal has never recovered. It is tempting to see this as evidence of water getting revenge on humans for our part in the Hydroplutonic Conspiracy.

At Gwennap Pit, an open-air oratory fashioned from an area of mining subsidence used by John Wesley, founder of Methodism, we gather to hear agrosopher Paul Chaney talk of ‘the new industrial human’. He tells how previously agrarian communities went from a reliance on the earth and God’s generosity to exploiting that earth without any reciprocal relationship. It seems a day that started with the birth of the universe has brought us back to the realities of the present.

Though everything we have heard speaks of underground and hidden histories, the effect is to focus our attention on the surface, the actual and the now. By peeling off the romanticised skin of Cornwall and forcing us to peer into its guts, Urbanomic have implanted the knowledge of the conspiracy in us all. Nowhere will ever be quite as it seems again.

Photographs by Coline Milliard and Jenny Haughton.

Read more about Urbanomic and Field Trip 3: Hydroplutonic Kernow in the Programme listing.