Field Trip 5: Teleport – Adam Chodzko’s response

Adam Chodzko was asked to give his response to the Teleport field trip to the Lizard peninsula. He has sent the following text as a record of his presentation at the Convention on Sunday 23 May. He writes: ‘Attached is my memory of my field trip response. It is taken from a few sketchy notes I made at the time and tries to fit with the sequence of images I showed (which I know are in the correct order). So I guess it is the skeleton of my talk as I remember it now in Cove Park, 17 July 2010.’

It’s been two days since the Teleport field trip. Our experience of it is evolving, eroding and accumulating in relation to what has happened since, and what we anticipate happening next.

‘There’s a storm coming’, said Andrew Nairne. But perhaps it will be a productive one. Not one that annihilates. In order to survive we have to change how we live.

I live in a kind of ‘rural’ with many of the same possibilities and problems as here. But here is better, whereas my ‘rural’, in relation to the capital, is in the shadow of the ‘big house’.

I think yesterday Hans Ulrich Obrist quoted Rem Koolhaas: ‘The future is the countryside’.

Or was that John Prescott?

The outer urban where I live doesn’t really know what it is. Cornwall has a much clearer identity. Has (re)invented itself. And I always feel a very productive kind of defiance here.

So, Telecommunication! Dematerialisation. Of place. ‘The end of geography.’ (There is no periphery).

Yet also the specificity of place. These points in the landscape are crucial and will never be repeated. As is our encounter with them.

The recurring question as our group began to meet each other is ‘so, where are you from?’

The evolution of our group dynamics

About a group. How we stood together, how we talked with each other and how that talking evolved – an inadvertent by-product of our sharing of an experience.

Teleport; transmission of data. A fantasy of our own dematerialisation and rematerialisation across time and space.

And here we are in state of transmission.

Steve Rowell and Daro Montag, clearly did huge preparation and research for this trip yet acknowledged their position as ‘outsiders’ by the inclusion of a series of incredibly enthusiastic local experts.

Our bus would pull into a lay-by and an expert would get in and guide us through the complexity of local communication history.

The quantity of detail and exactitude and pleasure with which they mediated these sites was remarkable. It was information that flowed but was impossible to contain or consume.

There is no periphery. But clearly we experience this as an edge. And in this bit of Cornwall all the big settlements are on this edge.

Is information the same when transmitted as when received? What is the delay or duration? Is this a series of vectors, or a flow?

Up and down the coast from Falmouth lie landing sites for the world’s submarine telecommunications cables, carrying the bulk of Internet and phone traffic to and from the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. At Bude to the north, Sennen and Porthcurno on the Penwith Peninsula, around Lizard Point and up to Kennack Sands – data flows by the terabyte.

Wireless communication history was also made in Cornwall with Marconi’s first transatlantic broadcast to St John’s in Newfoundland from Poldhu in 1901. Satellite communications were first brought to England via an earth station built in 1962 at Goonhilly Downs, transmitting TV signals via the Telstar 1 satellite orbiting 6,000 km above.

Despite or due to our environment a conversation over lunch was the attempt to remember every RCA curators’ course degree show.

We couldn’t. At least not in the right order and with work displaced from its existence in one show and now imagined in another.

In relation to art, remember the comment from earlier: ‘We just want good art…not work which is just good enough.’

So, here is the means, but what is the content of all this telecommunication? Given the opportunity do we have anything worth saying?

Look at the following evolution of content during the first successful transmission of our voices and then our appearance:

Samuel Morse stretched a wire between Washington and Baltimore in 1844. The first message he sent with his code was ‘What hath God wrought!’

1876: The first sounds transmitted down a wire were Alexander Graham Bell saying ‘Mr. Watson, come here. I want you’.

1901: Marconi test to Isle of Wight: ‘Near m biat three tis n n …seems about the same.’

Marconi sent an ‘s’ code, for success.

1962: Goonhilly, the first transmission of Telstar video: the first words were: ‘There’s a man’s face! That’s the picture!’

The cable-laying frenzy that occurred during the late-nineties dotcom boom.

At a secret location on a Cornish beach: Apollo: enough bandwidth for 20 million people.

It is 6m beneath the beach so a child with a plastic spade might reduce your download speed.

At Goonhilly: Future World

We were advised not to ask the people who worked there about the future. Was this Andrew Nairne’s ‘storm’ approaching?

But we did ask and we were told: ‘The future will be exciting!’

Here are some images that I took on a previous visit to Goonhilly a few years ago. It was in the past. Pre-Future World (which has now closed down). It was a previous idea, a visitors’ centre which, in the final image, you can see packed up and very over.

But, as they say, what happens next will be ‘exciting’!

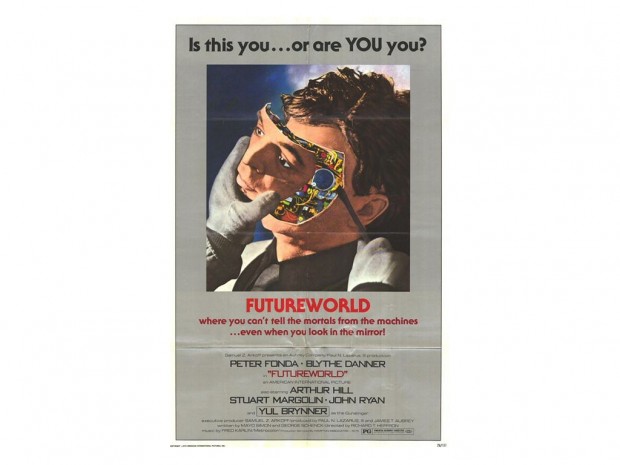

On the bus, entering Helston, Steve Rowell screened the trailer for the feature film Future World, ‘The ultimate vacation resort’.

‘It is safe!’ they keep asserting. It’s a trailer, so we know this information can only mean it’s going to be very unsafe.

The Future World film poster asks the question: “Is this you…or are YOU you?”

That makes my head hurt. So, we must move on to these final images.

So, here we are a few days ago looking at some ruins. But actually the ruins of the visitors centre for the Manifesta that might be held in Cornwall in a few years time.

Or maybe they are to look like that. Because, really, it is an artwork put in some years after the Manifesta happened, in the end, somewhere else. And they refer to the ruins of a fictitious visitors centre that might have been, but dematerialised, existing now only as its own ending and therefore the starting point for something else.

Photographs and text by Adam Chodzko.